History and Elaboration of Champagne

Initially, Champagne wine was not a sparkling wine. It was simply called "Champagne wine" between the 16th and 17th centuries.The process of making wine sparkling was discovered, according to legend, by the Benedictine monk Dom Perignon.

Pierre Pérignon, known as Dom Pérignon, was born in 1639. He was a Benedictine monk who, according to the legend, imported the method of making wine sparkle (second fermentation by adding sugar and yeast). Thus, was born the so-called Champagne method (Méthode Champenoise). He is therefore considered as the inventor of champagne. He was neither a winemaker nor an alchemist. At the monastery of Hautvillers, near Épernay, he oversaw the vines and presses of the abbey. His contribution to the method consisted in matching grapes of different origins before pressing them.

However, this method was approximate. Scientific progress, such as the work of Louis Pasteur on fermentation, made it possible to fix the effervescence. Historically, Ruinart was the first to offer sparkling champagne wine in 1729.

With an image of a luxury product well anchored in the mentalities, champagne tends however to be democratized. It is becoming more and more part of our daily festive habits and is increasingly appreciated as an accompaniment to meals.

The champagne market today has an annual turnover of 4.74 billion euros worldwide, almost half of which is achieved through exports. Champagne producers are moving off the beaten track and offering high quality champagne at more affordable prices, while respecting the specifications linked to the appellation.

The vineyards of the Champagne region

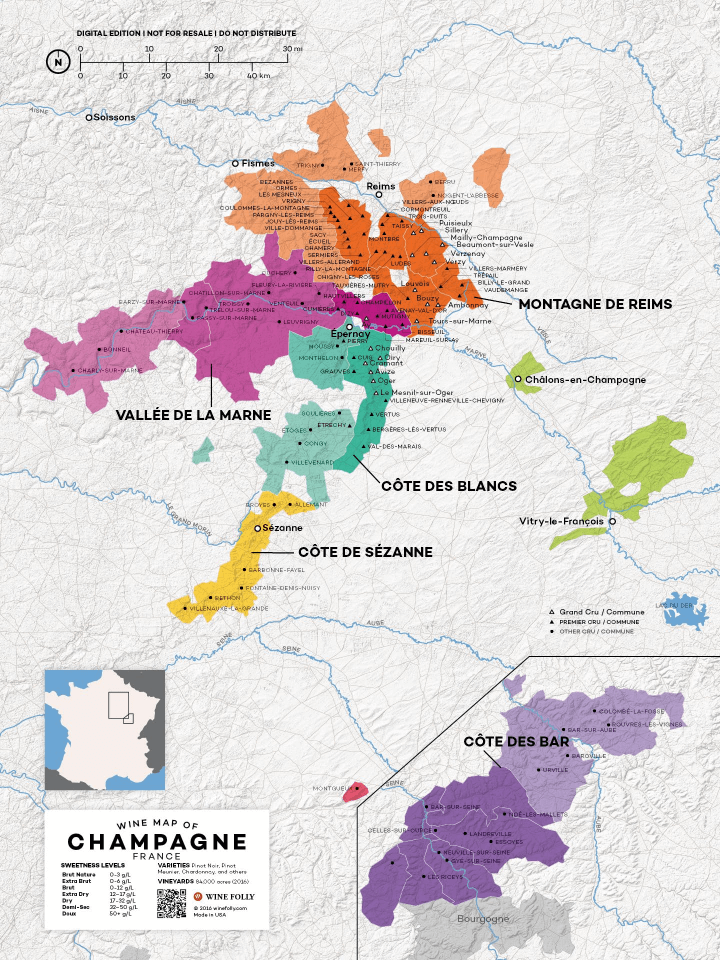

The grape vineyard is divided into four regions:

* LaMontagne de Reims

* LaVallée de la Marne

* LaCôte des Blancs

* La Côte des Bar

In the Champagne, the vines are grown in 319 villages and communities (called crus). These crus are rated on a scale from 80 to 100 as they differ in soil quality, microclimate and sun exposure, which are particularly conducive to producing the best grapes.

The vineyard (Climate, soil and grape varieties)

Champagne is a protected appellation and comes exclusively from Champagne region in France.The production methods are strictly regulated. The yield per hectare is limited. Champagne accounts for only 10% of the world's sparkling wine production.

An oceanic transitional climate:

* Mild temperatures (annual average of 10 degrees Celsius)

* Limited sun exposure, compensated for by the relief of the slopes

* Regular but moderate rainfall

* A climate that brings freshness to the grapes

A calcareous subsoil:

* An exceptional subsoil from a geological point of view

* A poor substrate from which the vines draw their own strength

* A natural regulation of heat and moisture

* This subsoil gives the champagne its mineral notes .

Grand Cru, Premier Cru and appellation of Champagne

In the Champagne, the vines are grown in 319 villages and communities (called crus). These crus are rated on a scale from 80 to 100 as they differ in soil quality, microclimate and sun exposure, which are particularly conducive to producing the best grapes.

The 255 remaining communes "non-vintage" are known as Champagne or AOC Champagne and cover around 21,000 hectares, or 70% of the total area.

-

The Grands Crus

Receive the highest score (100). 17 villages and communities (4,000 hectares) currently enjoy this exclusive status (e.g. Ambonnay, Avize, Aÿ, Bouzy, Cramant, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Tours-sur-Marne). Only a little more than 10% of the Champagne vineyards are declared as Grand Cru.

-

The Premiers Crus

Must have a score between 90 and 99. 44 municipalities can currently boast this title, including Chouilly, Hautvillers and Mareuil-sur-Aÿ. Approximately 15% of the total vineyard area is classified as Premier Cru.

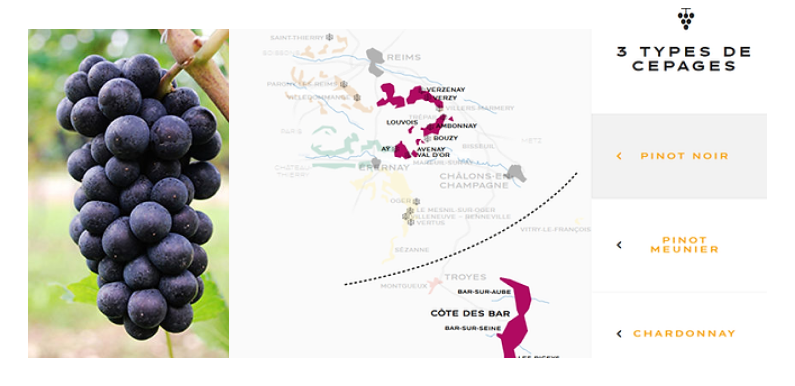

The 3 grape varieties of Champagne

The characteristics of the terroir have led to the selection of the grape varieties that are best adapted to the natural conditions. Today, Pinot Noir (red grape), Meunier (red grape) and Chardonnay (white grape) are the main varieties. Arbanne, Petit Meslier, Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris (all white grape varieties) are also permitted and make up less than 0.3% of the vineyard area.

Pinot Noir

38% of the planted vineyard area in the Montagne de Reims and on the Côte des Bar. Pinot Noir gives the blend strength and volume. It gives a white juice because the skins do not have time to color the juice during pressing, producing a well-structured wine with a fine bouquet.

Pinot Meunier

32% of the planted vineyard area mainly in La Vallée de la Marne. Meunier wine has a sweet and fruity taste, it develops relatively quickly and completes the blend.

Chardonnay

30% of the planted vineyard area in the Côte des Blancs. Chardonnay wines have a fine aroma with a floral note, fresh and delicate, a hint of citrus fruits and partly mineral notes. Due to the slow maturation they offer ideal conditions for the aging of the wine.

The grape variety is essential for the names Premier Cru and Grand Cru. Only Pinot Noir and Chardonnay can achieve Grand Cru status. The Grand Cru and Premier Cru status play an important role in the remuneration of the winemakers. The raw material price set by the CIVC association is paid 100% for the Grand Crus and for all other Crus according to their classification on the 80-100 scale. However, the winemakers are free to negotiate the price with their buyers.

A champagne can only be called Grand Cru or Premier Cru if all the grapes come from the communes declared as Grand Cru or Premier Cru. A Grand Cru or Premier Cru Champagne does not necessarily have to be made up of 100% grapes from a certain commune, but grapes from different communes with the same appellation can also be blended. A blend of grapes from different communes can benefit from these appellations. If a Grand Cru (or Premier Cru) village appears on the label of a bottle (e.g. Cramant), this means that all grapes come from this village. This is a proof of origin.

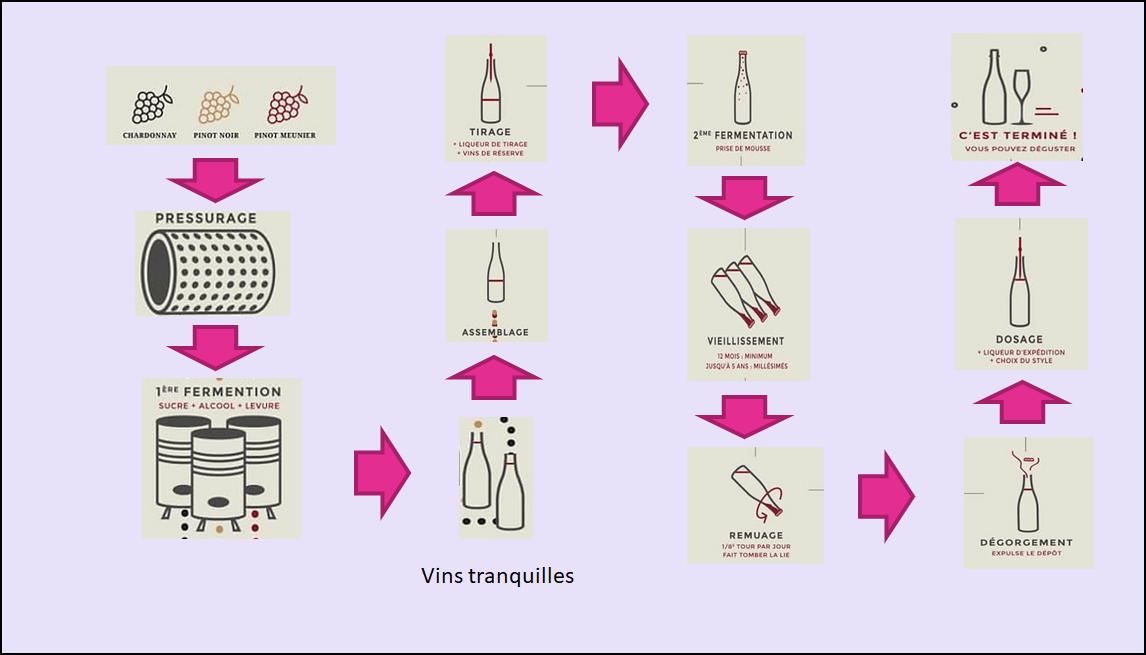

The Main stages in making Champagne: The Champagne method

The harvesting of the three grape varieties

In Champagne,the grapes are picked very carefully and entirely by hand because the bunches must be harvested whole so that the grapes arrive intact on the presses.

Pressing

The creation of champagne begins like the vinification of wine. The grape varieties, which can be black (Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier) or white (Chardonnay), are harvested and then directly pressed to keep only the grape juice in the vat (must).

As winegrowers and winemakers are always looking for the best quality, the pressing technique is governed by strict and often updated regulations.

As soon as they are picked, the bunches of grapes are taken to the "vendangeoir" where the presses are located.

The grapes are pressed there, vintage by vintage, variety by variety, and never wait more than six to eight hours, day, or night.

Champagne grapes are "the most expensive in the world" because each plot is cultivated like a small garden with a minimum of 8 000 vines per hectare! The equivalent of all the fruit on one vine will be needed to make one bottle of this wine.

Alcoholic (and sometimes malolactic) fermentation

The juice will then begin its alcoholic fermentation and will become wine (a stage in which the sugar is transformed into alcohol).

The alcoholic fermentation takes place in temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks. In the first five or six days, the fermentation results in the effervescence of the grape juice , which gives the impression of boiling.

The winemaker then uses various techniques to regulate the temperature , most notably by circulating a coolant. It has to maintain a constant temperature of 16° to 20°C in order to favour regular fermentation without evaporation of the aromas.

The must or grape juice is then transformed into a still wine (obtained at the end of the first vinification cycle) by transformation of the last grams of sugar, a process that is completed in a period of 15 days.

This white wine may eventually undergo malolactic fermentation. After alcoholic fermentation, the winemaker keeps the wine at a minimum temperature between 18° and 20°C.

Malolactic fermentation is less intense and less visible, but takes longer than alcoholic fermentation requiring four to six weeks. This fermentation gives the wine less acidity, more suppleness, a refinement of the aromas and ensures great future stability.

On the other hand, wines that have retained their malic acid (without malolactic fermentation) are fresher, more acidic, fruity and have a longer shelf life. For this reason, some Champagne Houses prefer not to do malolactic fermentation. Once the alcoholic and malolactic fermentation is complete , the wine is gradually cooled between 10° and 12°C.

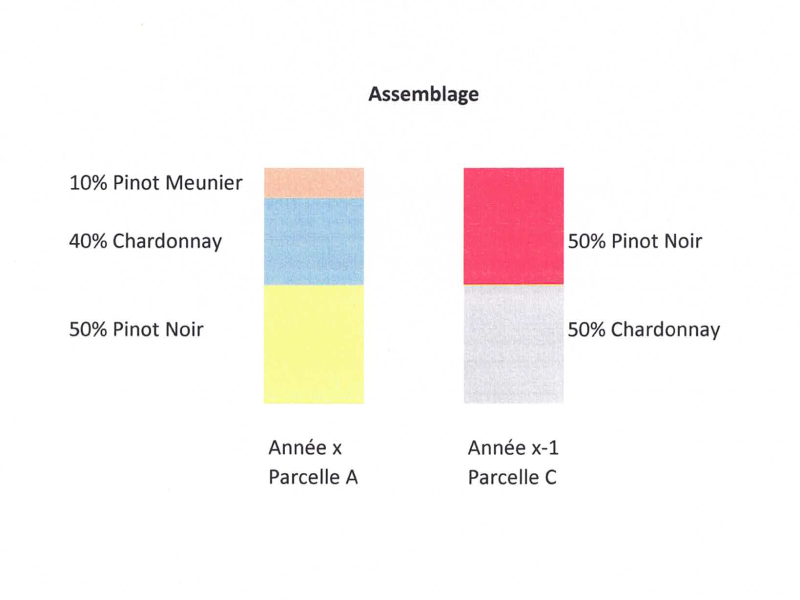

Blending

After the first fermentation, the Cellar Master and his oenologists will undertake the blending of complementary wines from different vintages, grape varieties and years in order to find each year the taste that defines the reputation of the House. This is an essential and fundamental step in maintaining the House's brand image. Only their experience and their palate will guide their choice in search of excellence.

From January onwards, the Cellar Master will taste and analyze the wines, essentially relying on his sensory abilities. Since the wines vary with each harvest, he has to taste and smell the different vintages every year in order to get a very precise idea of the proportions that lead to the perfect combination of taste and aroma . He first blends wines from the same or neighboring crus in order to obtain a homogeneous cuvée.

He then blends them in such proportions that the fineness, character, alcohol content and aroma are optimal. These combinations are repeated several times after testing, tasting and comparison. They are then processed in large vats to ensure the desired perfect homogeneity.

«Tirage» and second fermentation

The term "tirage" refers to all the operations involved in bottling the still wine obtained at the end of the first vinification cycle. At this stage, known as the "prise de mousse", a second alcoholic fermentation takes place, during which carbon dioxide (CO2: the result of the yeast "eating" the sugar) is created as well as the formation of the future bubbles and foam of wine. To do this, the winemaker prepares his "liqueur de tirage" from still wines, to which he adds a small amount of sugar and active alcoholic yeasts .

By law, bottling may not take place before January 1st of the year following the harvest. Depending on the size of the House, it can last from a few days to seven or eight months.

The precious champagne bottle can be any size. Eight different bottle sizes are regulated in the European Union:

* le quart: 20 cl

* le Demie: 37.5 cl

* la Bouteille: 75 cl

* le Magnum: 1.5 liters (2 bottles)

* le Jéroboam: 3 liters (4 bottles)

* le Réhoboam: 4.5 liters (6 bottles)

* le Mathusalem: 6 liters (8 bottles)

* le Salmanazar: 9 liters (12 bottles)

Some others are custom made to special order:

* le Balthasar: 12 liters (16 bottles)

* le Nabuchodonosor: 15 liters (20 bottles)

* le Salomon: 18 liters (24 bottles)

* le Melchizédec: 30 liters (40 bottles)

The slow awakening of the aromas: the maturation

The yeasts die, burst and turn into lees, which slowly enrich the wine with amino acids, proteins and volatile components. This gives the wine its complex aromas and fine foam. This phase of patience awakens the wine, which is enriched with aromas and flavors during these weeks. This working phase of the wine is a fundamental one. It is the combination of all these methods and knowledge that ensure the consistency and quality of a champagne wine. The rules for the appellation "Champagne" stipulate a minimum storage time in the cellar of fifteen months before marketing and three years for the "Millésimés" from the date of bottling.

In practice, most winemakers allow their wines to mature much longer than the required minimum time, taking into account that the Meunier ages faster than the Chardonnay, which is more lively.

Every House retains its own know-how and has its own secrets well hidden and protected.

«Pointage» and stirring

The bottles are inclined on an oak easel at about 35° (pointage). The Cellar Master, also known as a "remueur" taps his wrist to remove the deposits from the glass and makes it easier to slide towards the neck of the bottle. This operation will take three weeks . By holding them by the bottom, the Cellar Master gives the bottles a short, dry rotation on the bottles, sometimes to the left and sometimes to the right, to remove the heavy deposit. Over the weeks he gradually straightened them little by little to bring them upright, head down.

These long and laborious movements are necessary to make the deposit (very often dead yeast) fall. They are carried out manually or automatically.

"Disgorging"

"Disgorging" means the expulsion of the deposit in the bottle under the action of internal pressure. For the winemaker, it is a matter of uncorking the bottle that has previously been brought back upright.

The dosage

The disgorging has left a void in the bottle that must now be filled. Moreover, the natural acidity of the wine and the carbonic gas being high, it is necessary to sweeten the contents, depending on whether one wishes to obtain a " doux", "demi-sec", "sec", "extra-dry", "brut", "extra-brut" or "brut nature" wine. This is the role played by the "liqueur d'expédition" (or "liqueur de dosage") which is a mixture of very pure cane sugar and old Champagne wines adapted to each cuvée. This liqueur has been prepared a few months before with reserve wine of at least tow years of age. It is the quantity of sugar added that allows the elaboration of different levels of taste, more or less dosed, i.e. more or less sweet, defined as follow in the European Union:

* "doux": more than 50 gramms sugar per liter

* "demi-sec": between 32 and 50 gramms sugar per liter

* "sec": between 17 and 32 gramms sugar per liter

* "extra-dry": between 12 and 17 gramms sugar per liter

* "brut": less than 12 gramms sugar per liter

* "extra-brut": between 0 and 6 gramms sugar per liter

* "brut nature", "pas dosé" or "dosage zéro": between 0 and 3 gramms sugar per liter

The cork and the "muselet"

The role of the cork is essential because it is the guardian of the quality of the wine. The corking must be precise and even to ensure a perfect seal. Uncorking must be done without effort, but with a certain amount of restraint. As soon as the cork comes out of the neck, it should take the shape of a mushroom. In order to regain all these properties, the champagne Houses use cork as the only material for the production of the cork. The muzzle (muselet in French) consists of a "cage" made of metal plate with the manufacturer's name on it. The plate placed on the cork is tightened around the cork to prevent the cork from popping out under pressure. The often decorated plates serve the brand image of the Houses.

The coating of the bottles

This step is the final touch before marketing. As with the other operations, the decoration of the bottle is more or less mechanized.

Prestigious bottles are generally hand coated because of their particular shape and the small series they represent. On the other hand, standard bottles are finished at a rate of 900 to 8,000 bottles / hour.